The first seven months!

Short essays by Douglas Winslow Cooper, Ph.D., the author of TING AND I: A Memoir of Love, Courage and Devotion, published in September 2011 by Outskirts Press (Parker, CO, USA), available from outskirtspress.com/tingandi, Barnes and Noble [bn.com], and Amazon [amazon.com], in paperback or ebook formats. Please visit us at tingandi.com for more information.

Monday, February 21, 2022

Saturday, February 19, 2022

"Save Science from Covid Politics"

Ten crucial lessons from Dr. Vinay Prasad.

How to Save

Science From Covid Politics

Ten crucial lessons from Dr. Vinay Prasad.

Scientific knowledge is

supposed to accumulate. We know more than our ancestors; our descendants will

know far more than us. But during the Covid-19 pandemic, that building

process was severely disrupted. Federal agencies and

their officials have claimed to speak on behalf of science when trying to

persuade the public about policies for which there is little or no scientific

support. This ham-handedness—and especially the telling of “noble lies”—has

gravely undermined public trust. So has the hypocrisy of our elites. Look no

further than the Super Bowl, at which celebrities and politicians had fun

mask-free, while the following day children in Los Angeles were forced to don

masks for school. The upshot is that

science and public health have become political. We now face the very real

danger that instead of a shared method to understand the world, science will

split into branches of our political parties, each a cudgel of Team Red and

Team Blue. We cannot let that

happen. Thanks to protective

vaccines, a huge number of Americans with natural immunity, and a less lethal

strain of the disease, now is the time to talk about how to undo the grave

damage that has been done. To avoid similar pitfalls when we are faced

with the next public health emergency—and to rectify the mistakes that are

still unfolding—here are ten crucial lessons: Identify the Most

Vulnerable Covid is far more

dangerous to older people than younger people. The risk difference by age is

the single largest epidemiologic risk gap I have ever seen in

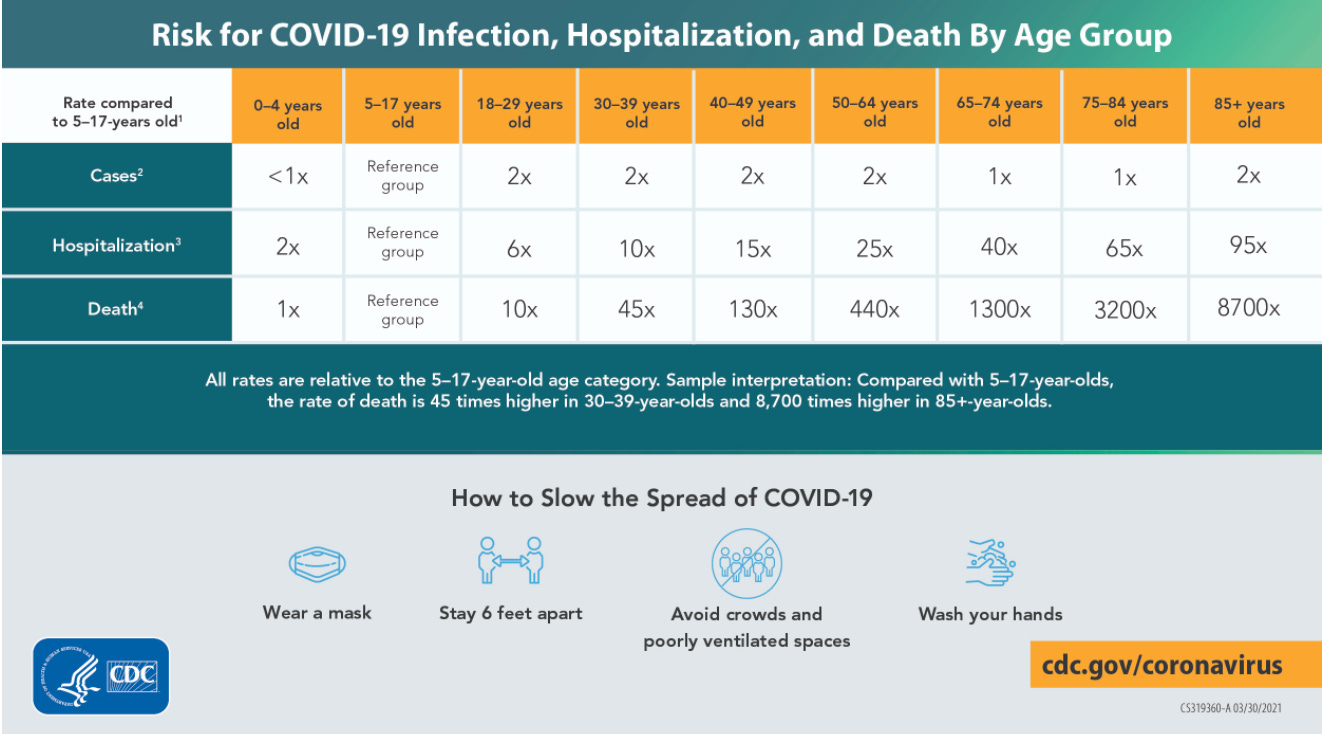

biomedicine. The image below, put out by the CDC one year

into the pandemic, shows that an 88-year-old has 8,700 times the risk of

death of an 8-year-old. This astounding risk differential was known in the

very early months of the pandemic. But it was consistently ignored by policy

makers who pursued one-size-fits all restrictions with vigor. Scientists that

advocated for a more nuanced approach—do more to protect older people, and put fewer limits

on younger people—were demonized. Protect

the Most Vulnerable We knew early on that

older people were the most vulnerable to this disease. That’s why then New

York governor Andrew Cuomo’s decision to force nursing

homes to accept residents back when they were sick

with Covid-19 is not just terrible in retrospect, but was clearly disastrous

at the time. Yet somehow the U.S. hasn’t learned from this and similar

disasters: We are still failing to adopt policies that focus on addressing

stratified risk. Others have done better. In England, among people older

than 65, just 4 percent are unvaccinated and just 9 percent are unboosted.

Compare that to the U.S., in which 12 percent of Americans in this age group

are unvaccinated and 43 percent are unboosted. Rather than focusing on this

population, which indisputably benefits from boosters, the White House has

been obsessed with a one-size-fits-all booster policy, lumping together

12-year-olds with 82-year-olds. Putting aside the fact that there is a

legitimate debate about whether boosters are necessary for the young, this

heavy-handed strategy is distracting us from the morally urgent task of

protecting the old. Liberate the

Least Vulnerable Meanwhile, college kids

are subject to a barrage of unnecessary restrictions, such as frequent

testing, bans on eating in the dining hall, universal mask mandates, booster

requirements, limitations on socializing and a host of other anti-scientific

policies that have led to isolation, distress and depression. Students are asked to snitch on one another if they see

violations, such as lowering a mask. And for what? A healthy,

vaccinated college kid is as protected as anyone can be from the coronavirus.

The risk of a person ages 15 to 24 dying of

Covid or even with Covid (CDC stats don’t separate this out) is 0.001

percent. Some believe that these

restrictions are meant to protect faculty, but faculty face far greater risk

off-campus when they participate in dinner parties, vacations, and travel.

They are not being forced by administrators to give up many of the things

that make life worth living. Neither should students. Fight for

Normalcy Children, who face the

least risk from the virus, have been subjected to the most damage. They have

been treated as vectors, not as human beings, and we’ve justified it by

saying that they are “resilient.” Those who have fought for normalcy for kids

from the beginning—especially parents—have been ignored and denigrated. At last, the dam is

breaking. Recently dozens of op-eds have lamented what has been the greatest

crisis of the pandemic: our treatment of children. They have faced

two years of disrupted education; continue to wear masks with no end in sight

in many locations (both indoors and outdoors); and are constantly subject to

testing, quarantining and pauses in school. Proportionality is a

cardinal principle of public health ethics, and we must restore it for our

children. The Urgency of Normal is a group of doctors

and scientists—I am one—who have created a toolkit for policy makers, showing

the way to return the joys of childhood. Clear limits and checks must be

placed on the state to prevent this from ever happening again. Learn from Other Countries We have been foolish not

to learn more from the experience of other countries.Vaccine policy varies

widely across Europe, which treads lightly with younger people. Some nations have decided against vaccinating

healthy kids between the ages of 5 to 11, and reserve it only for kids with

comorbidities. Others have been reluctant to give a second

dose to adolescents, uncertain if the risk of myocarditis—an inflammation of

the heart muscle—exceeds the additional gain from a second shot. On closures and masking,

we have also been out of step. The World Health Organization advises against

masking children under 6, and only selectively under 12—policies followed by

many European countries. Many Western European nations closed primary school

just for a few weeks, not years, and Sweden famously never closed grade

school. Norway has stopped testing kids for mild symptoms and

only keeps them out of school if they feel sick. These are all eminently sane

policies that take into account children’s rights and wellbeing. Run Randomized

Trials In medicine, it is often

hard to know the effect of our interventions or policies. This is for three

reasons: Most policies don’t work; those that do generally offer modest

benefits; and we are an incredibly hopeful and optimistic species. These

facts mean that doctors, scientists, policy makers and patients easily fool

ourselves into believing that what we hope will help actually does. (I

wrote an entire book on flip flops in medicine, which

largely occur because of wishful thinking and getting ahead of evidence.) Let’s say we want to find

out if a particular policy—say, mask mandates—actually helps. A randomized

trial is a tool that allows us to separate the biases of the world—some

states are blue, some people take more precautions, some places have higher

vaccine rates—and lets us figure out the actual value of an intervention. By

randomly assigning groups to either have the intervention or not, you balance

out the variables and isolate the effect of the mandate. Many experts have called for more randomized trials during the pandemic. But

they were ignored. We should have studied whether social distancing works,

and how much distance is ideal. We should know a lot more about who to test,

why we’re testing, and how often to test. Even school closure and reopening could have

been studied. Randomized trials could have turned political fights into

scientific questions. Not running them was a huge failure. Don’t Promote

Shoddy Studies During the pandemic the

CDC has developed a track record of promoting flawed studies to support their

preconceived policy goals. Most notorious was an Arizona State University

study highly touted by the organization (and published in their journal MMWR)

that sought to justify mask mandates in schools. Journalist David Zweig, writing

in The Atlantic, thoroughly debunked the study, making the

convincing case that it was so flawed it should not have been

published. But the CDC did not stop

there. I published detailed critiques of several more studies promulgated by

the agency to support the White House’s policy goals. One claimed that Covid causes diabetes in kids, but failed to

adjust for the body weight of the children, a crucial metric. (A more recent analysis from the UK finds no

such association.) Another claimed that people who more rigorously wear cloth

masks have 56 percent lower odds of testing positive for Covid-19. The paper

was so irredeemably flawed that it should never have been published, as I outline here. Don’t Ignore

Inconvenient Facts Don’t ignore scientific

facts just because they don’t fit a policy imperative. For example, for most

people, a Covid-19 infection results in a substantial immune response—what’s

called “natural immunity.” But our officials, because of their singular focus

on vaccines, have essentially ignored this basic fact, pretending natural

immunity doesn’t exist. The distinguished vaccine

expert Dr. Paul Offit recently co-wrote an op-ed with former FDA employees

Luciana Borio and Philip Krause explaining that people who have been infected

with Covid should only have to get one dose of vaccine, not the three now

recommended by the CDC. If natural immunity means people don’t need multiple

shots—and I believe this is the case—our experts should say so. By ignoring

the reality of natural immunity in favor of their desired policy of triple

vaccination, our officials are not making us safer. They are undermining the

trust that is essential between the experts and the public. Don’t Stifle

Debate The pandemic befell us

during the rise of cancel culture, which has captured so many of our

institutions. Calls to censor, silence, de-platform scientists and others who

disagree with official policy have been vociferous and very nearly constant.

When faced with an unprecedented public health threat—and in a time when our

culture responds in an unprecedented manner to disagreement—perhaps it was

inevitable that crucial debates would be stifled and that dissidents would be

smeared. And that’s exactly what happened. Scientists who came out

early in favor of focused protection of the elderly were labeled “fringe” by

the NIH director Francis Collins and were quickly

demonized. The chilling effect of this public denunciation was real. I

know many like-minded junior faculty who refrained from commenting on Covid,

fearing personal and career retribution. Facebook infamously censored the lab leak hypothesis,

only to recant, when the journalists Nicholas Wade and Donald McNeil showed

that this was a story that needed exploring. Empowering massive technology

companies with the ability to censor anyone is dangerous for an open society.

I investigated Facebook’s third-party censors

and found that in one instance, they selected a “fact checker” who had

already tweeted criticism of the article they were asked to check. This is

akin to selecting a juror for a trial who already stated she believes the

defendant is guilty. There is a real solution

to information you do not like or that you disagree with: A detailed,

methodical rebuttal. Not theatrical calls to silence the speaker. Don’t Destroy a

Brilliant Legacy We should rightly be

celebrating the magnificent breakthrough of the mRNA vaccines, which were

quickly developed, saved millions of lives, and hold the promise for further

medical advances benefitting all humanity. We also now have (when doctors can

get them) effective medications for vulnerable people who contract

Covid-19. Of course, a global

pandemic will result in many wrong decisions, missed opportunities, and

inevitable tragedy. But during this one, our officials have too often misled

us, failed to make timely corrections of mistakes, doubled down on a foolish

policy that simultaneously overburdened the young and neglected the elderly,

and thus severely undermined public trust. I fear all this will be our

Covid-19 legacy. Dr. Vinay

Prasad has consistently been able to cut through the noise, the confusion,

and the politics that characterize our public conversation about Covid-19. If

you missed him on Honestly, listen here:

And if you

appreciate pieces like this one, please subscribe:

Thanks for subscribing to Common

Sense. This post is public, so feel free to share it. © 2022 Bari Weiss Unsubscribe |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Monday, February 14, 2022

REVIEW OF SUPERSURVIVORS:

The authors skillfully mix true stories of supersurvivors with their professional insights and with the results of studies they cite, as these “two psychologists explore the science of remarkable accomplishment in the wake of trauma.”

A cancer survivor gives up her

profession to pursue her dream of becoming a professional violinist and

succeeds astoundingly, though postponing having a risk-reducing operation and waiting

for the opportunity to marry and have children she has long wanted.

A nearly blind man rows across the Atlantic, risking death,

conquering his fears.

An African refugee learns to forgive those who tortured and humiliated

her and finds new hope in reuniting with her family.

The authors argue that “positive thinking” is not the key to

supersurvivorhood, as some of these achievers had positive views of the world,

and some were less favorably disposed. Rather, what seemed key was to have a rationally

grounded belief in the likelihood of their personal triumph.

Of the many interesting and useful studies the authors cite,

I was particularly struck by the one comparing the outcomes of job searches by

a set of college students who were Optimizers versus the outcomes for a similar

set who were Satisficers, who had not sought the “best” but rather the “good

enough.” The Optimizers ended up with significantly higher salaries, but were

less pleased with their outcomes than were the Satisficers.

This reader came away with admiration of those profiled and appreciation

of the significance of belief in ourselves, tempered with the rational appraisal

of the challenges we face.

I help would-be authors to write and publish their books, through my endeavor,

Tuesday, February 8, 2022

Leo Cooper Chiang's First Six Months

Is there a record for being adorable? Call Guinness!

My grandson is in the running.

Actually, the crawling.

Whatever.

https://photos.google.com/share/AF1QipNHzMgaQUP1Klbk--L0pRd4r5NIPAATrwH67aDsxUxcSvvZER5cJ2T88Dt5z9_lyA?key=ZnhxZDZtSWY2THBvZHpiU1VMaXNmRmpzZlp3aGZRArticle: Applying THINKING IT THROUGH Problem-Solving

Westport Rotarian’s Book Helps Sharpen Problem-Solving Skills

Feb 7, 2022 | Community, Education | 0 comments

By Gretchen Webster

WESTPORT — There are plenty of problems to solve in the world today, both collectively as communities, and in individual lives and careers.

Michael Hibbard, PhD, of Westport, after years of research, has designed a method to help people learn how to problem solve effectively. After a presentation about his book, “Thinking It Through,” to the Westport Sunrise Rotary Club, he is coaching Rotary members how to bring the problem-solving process to their jobs.

On a recent Wednesday, Hibbard met with Westporter and Sunrise Rotary member Kola Masha, the founder of a company that helps farmers in Africa transition from subsistence to commercial farming, to train him as a coach in Hibbard’s problem-solving methods.

“I’ve been very interested in the idea of developing creative and problem-solving skills,” Masha said. “It’s exceptionally exciting to see someone with his depth of experience willing to share it with the world.”

Hibbard’s experience in education spans 47 years, as a teacher, principal and administrator. He was a teacher and dean of students in the Greenwich public schools where he developed a science program for elementary students; a high school principal and assistant superintendent in Connecticut’s Middlebury-Southbury school system; spent 10 years with the Ridgefield schools, and was recruited by North Salem, N.Y., schools as an assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction, where he worked for 10 years. He earned a master’s degree in biology at Purdue University and a doctorate in science education at Cornell University.

Now retired, Hibbard consults nationally and internationally on bringing problem-solving skills to students and to business leaders.

In North Salem, teaming with colleague Patricia Cyganovich, his research on the thought processes involved in solving problems coalesced into the book, “Thinking It Through: Coaching Students to Be Problem-Solvers,” published last fall.

“COVID actually gave me a lot of time for researching, writing and going to business people. I kept asking, ‘What is valid and useful, valid and useful?’ over and over,” he said.

Navigating the steps of problem solving

“Thinking It Through” offers a six-phase process to organize thinking around problem solving. Among the phases are identifying the problem, analyzing who the stakeholders and beneficiaries would be for the solutions to the problem, and generating several ideas for a solution.

He discovered that one of the biggest obstacles to successful problem solving is that people often disagree with each other over solutions to a problem. “People are fighting over solutions and they don’t understand even what the problem is,” Hibbard said.

“The reflex reaction is to jump into a solution in one second, and fight about it with people who have their own solutions,” he said. Or when faced with a problem, “They use the same old, ‘This solution worked before, OK, let’s just do it again,’ ” method of problem solving, he said.

Among other techniques, learning to be a person who disagrees without anger and hostility, helps make problem solving better, Hibbard added. “Problem solving is naturally connected to disagreements — if you were more agreeable you would get more work done,” he said.

His goal now is to train others to be coaches using his problem-solving method, so that they can coach others in their own organizations. He especially hopes to reach out to other Rotary Clubs with his presentation and has already been asked to speak at some area clubs.

“Problem solving has become a more and more essential characteristic that more and more people realize is a crucial skill,” he said.

###

I was honored to be coach and editor for Drs. Cyganovich and Hibbard through my Write Your Book with Me endeavor.

Their book is published by Outskirts Press and is available at amazon.com, among other online booksellers: